Lyric Theater

1800 Third Avenue N,

Birmingham,

AL

35203

![]() 6 people

favorited this theater

6 people

favorited this theater

Related Websites

Lyric Theater, Birmingham (Official)

Additional Info

Previously operated by: Keith-Albee, Paramount Pictures Inc., Wilby-Kincey

Architects: Claude Knox Howell

Functions: Concerts, Live Music Venue

Styles: Beaux-Arts

Previous Names: Grand Bijou Theater, Foxy Adult Cinema, Roxy Adult Cinema

Phone Numbers:

Box Office:

205.252.2262

Nearby Theaters

News About This Theater

- Aug 10, 2013 — Looking back at Alabama movie palaces

- Oct 11, 2012 — Lyric Theatre returns with huge benefit

The Lyric Theater opened January 14, 1914 as a vaudeville theatre with 1,583 seats located in orchestra, mezzanine and upper balcony levels. It was a segregated theatre where African-Americans would sit separately in the upper balcony, which had its own entrance on 18th Street N. It was operated by the B.F. Keith circuit and stars such as Rube Goldberg, Fred Allen, Jack Benny, The Marx Brothers, Buster Keaton Mae West, Sophie Tucker, Will Rogers, Milton Berle, Roy Rogers and Gene Autry appeared here. There were six opera boxes on each side of the proscenium, which were removed when the theatre was equipped for CinemaScope in 1954. Above the proscenium is a mural titled “The Allegory of the Muses” painted by local artist Harry Hawkins. In 1925 a Kilgen 2 manual 4 ranks theatre organ was installed. The Lyric Theatre was closed as a regular movie theatre in March 1960.

It reopened on April 19, 1973 as the Grand Bijou Theatre with Al Jolson in “The Jazz Singer” and specialized in screening classic movies, but this was not a success. It went over to adult movies first as the Foxy Adult Cinema, and later as the Roxy Adult Cinema which closed in the early-1980’s. The building lay empty and unused and in 1993, the owners sold it for $10 to Birmingham Landmarks. In 1998 plans were being formed to reopen the Lyric Theatre, but very little happened and the building began to deteriorate.

In March 2014, plans were approved for an $8million renovation to be carried out. The opera boxes have been re-instated, and the mural restored by Evergreene Architectural Arts, who worked on most of the internal restoration. The Lyric Theatre re-opened January 14, 2016 (102 years to the day of its initial opening) as a live music and concert venue. Seating has been reduced to 750 as the upper balcony is not in use.

Just login to your account and subscribe to this theater.

Recent comments (view all 23 comments)

Ladies and Gents, on Sep 28th, 2012, The Lyric Theatre hosted it’s first live performance in over 60 years. The event was a benefit concert by the Chad Fisher Jazz ensemble to raise funds for the continued restoration efforts for the Lyric. To accomplish this feat, volunteers laid down new temporary plywood flooring and lighting. Patrons brought their own chairs. Special dispensation was given by the City of Birmingham, Birmingham Fire Marshal and Code Enforcement to permit this special show. 200 tickets for this performance sold out in a matter of days.

Although the theater area has substantial water damage and decay, the sound quality was nothing less than astonishing. Live jazz spilled across the audience warm and rich as honey. There appeared to be clear sight and sound lines from all parts of the main floor. The band later reported that the sound quality and natural feedback from the venue walls was incredible.

http://savethelyric.com/ https://rally.org/savethelyric

what a beautiful old lady this theatre is..shame so many of her conteparies have already died….

Here’s a blog post with some recent photographs of the Lyric Theatre

Theatre is scheduled to reopen on 14 January.

Step inside the Lyric Theatre today, and you might feel as if you’re encased in a small, glittering jewel box. The 102-year-old theater fairly glows with historic charm, adorned by elegant plaster cupids, burnished wood, smooth marble and shimmering gold paint. Chandeliers hang from the ornately stenciled ceiling. Opera boxes curve in graceful arcs. Thick blue curtains shelter a stage that once welcomed stars such as Mae West, Sophie Tucker, the Marx Brothers and Milton Berle.

But it wasn’t always this way. The Lyric — built in 1914 as an intimate vaudeville house with pin-drop acoustics — spent decades in downtown Birmingham as a dark and crumbling ruin. The building’s essential structure remained strong, made of concrete and steel. But the theater at 1800 Third Ave. North existed as a shadow of its former self. Its heyday long past, the Lyric sat in silence — damaged by water and weather, prey to the ravages of time. “When we first got here, it was like King Tut’s tomb,” says Brant Beene, executive director of Birmingham Landmarks, a nonprofit organization that owns the Lyric. “It was really a sight to see.”

Birmingham Landmarks, which acquired the Lyric in 1993, spent more than 20 years figuring out how to revive the theater — and just as important, making sure enough money was raised to pay for such a massive project. Painstaking craftsmanship was required to bring the Lyric’s visual beauty back to life, along with a full-scale overhaul of crucial operating systems such as lighting, plumbing, heating and air conditioning.

In January, audiences saw the result of an $11.5 million restoration as the Lyric reopened to the public as a performing arts center. Three variety shows featuring local entertainers were sold out Thursday through Saturday, marking the theater’s triumphant return.

“I’ve had so many sleepless nights, and I’m sure Brant does, too,” says Danny Evans, board chairman of Birmingham Landmarks and a prime mover behind the Lyric’s revival. “The Lyric was abused for many years, but she’s a strong old girl. … For this to be complete, in spite of some naysayers who kept asking, ‘When are they going to do it?,’ is a great joy to me.”

Talk to organizers who’ve prompted the theater’s rebirth, and you’ll hear detailed accounts of feasibility studies, grant proposals, architectural renderings, preliminary plans, fund-raising efforts, tax credits and more. Some might call it a long and difficult journey, with many stops and starts. Evans, who was there from the beginning, prefers the analogy of building blocks slowly sliding into the proper spots. As he tells it, Birmingham Landmarks never intended to take on the Lyric when the organization was formed in 1987. However, the nonprofit’s basic mission — to save historic buildings — nudged the group in that direction when the Lyric became available a few years later.

According to Evans, Birmingham Landmarks was created for one purpose: to ensure the survival of the Alabama Theatre, a 1927 movie house that was facing bankruptcy. At the time, Evans and a piano-playing friend, Cecil Whitmire, were especially concerned about the theater’s Wurlitzer organ, a majestic instrument that was integral to the building’s history. Birmingham Landmarks bought the Alabama, assumed its debt of $680,000 and made that theater — across the street from the Lyric at 1817 Third Ave. North — the nonprofit’s primary focus. Evans helmed the board; Whitmire managed the theater. Under their leadership, the Alabama began to thrive.

The Lyric was something of an afterthought, purchased in 1993 from the Newman Waters family, along with a companion office building that stretches to 1806 Third Ave. North. The family, which had owned several movie houses in the Birmingham area, set a price of $10, essentially offering the Lyric as a gift. “It was a just a remnant of the vaudeville house it used to be,” Evans recalls. “It had a bad roof. The windows were falling out. It had been abused and used for many things, including selling beauty supplies. All that was dumped in our laps. We were able to get enough money to put a new roof on it and fix the windows, enough to keep it from deteriorating further. … We began doing feasibility studies on the Lyric. We did early architectural renderings and plans in the late ‘90s and early 2000s. In the middle 2000s, interest rates rose and the economy started tanking. We kind of moseyed along like that until 2008 or 2009.”

Although Birmingham Landmarks had a vision for what the Lyric could be, it faced a formidable challenge. The once-pristine theater had been through many structural changes since the glory days of vaudeville, first transformed into a movie house during the early 1930s. That period ended in 1958, when the hardest times hit. The Lyric closed, reopened for a few years in the 1970s as a revival house and had a brief run as a porn theater. The building was shuttered in the 1980s and left to decay.

“The Lyric was so well-built, it wouldn’t fall down,” says Beene, who joined Birmingham Landmarks in 2009. “The cost to demolish a building like that is so great, there wasn’t much talk about making it a parking deck. But nobody wanted to buy it. Nobody knew what to do with it.”

Whitmire, who died in 2010, often said fundraising for the Lyric was more difficult than it had been for the Alabama Theatre, mostly because the vaudeville generation had passed away. Potential donors lacked an emotional connection to the century-old building, he said, and cherished no fond memories of seeing live shows there.

Beene was hired by Birmingham Landmarks to combat such perceptions, kickstart the Lyric’s finances and stir community participation in the project. After Whitmire’s death, he moved into the executive director role and has overseen the Lyric and Alabama theaters ever since. “I think Cecil and Danny had to swim upstream for about 20 years, because things were moving away from downtown,” Beene says. “At one time, the Alabama Theatre was the only thing downtown. After Birmingham Landmarks was formed, it took 10 years, maybe 11, to get the Alabama to where they wanted it to be. They inherited the Lyric in ‘93, and the Alabama was only half-done at that point. The focus was on the Alabama. It seemed almost impossible, at least to Cecil, to raise the money they needed for the Lyric. And the Alabama was his first love. The Lyric didn’t have an organ. When he died, right at that time period, Railroad Park and lofts and Regions Field and all those things were starting here. I came in and caught the wave.”

As more fundraising, another feasibility study and a mountain of paperwork ensued, Beene sensed a shift in public attitudes about the Lyric. Millennials began to take notice, gushing over tours of the building led by volunteers such as Glenny Brock, then editor of Birmingham Weekly. Articles in that alternative publication, particularly those written by reporter Jesse Chambers, championed the theater and pointed to new life for the old vaudeville house. Brock, who later became outreach coordinator on the staff of Birmingham Landmarks, says her first visit to the Lyric in 2008 made her a believer. It led her to participate in cleanup sessions at the theater — pulling up carpet, scraping paint, mopping floors, removing dead birds and bat droppings. It also inspired her to spread the word about the Lyric and its potential — in print, online and in person.

“The Lyric, to me, was such a beautiful ruin,” Brock says. “The outside of the building, for much of my life, was very plain, like a brown cardboard box. It became a personal mission; I wanted to see it succeed … Most of my role, as this title implies, is making sure people know about the Lyric. Basically, I just tried to get everyone to love that place as much as I did.”

Others involved in the Lyric’s renaissance, such as lead fundraiser Tom Cosby, relied on the simultaneous pull of art, history and economics. Cosby joined the team in 2012 as a paid consultant for Birmingham Landmarks, after 35 years with the Birmingham Business Alliance and its predecessor, the Birmingham Regional Chamber of Commerce. Although he’d intended to retire, Cosby quickly became enmeshed in the mission to save the Lyric, using his experience, contacts and knowledge of Birmingham’s power players to get the job done. Spearheading a new “Light Up the Lyric” campaign that was launched in March 2013, Cosby raised more than $7 million for the theater in just nine months. A sparkling new marquee was installed that September, celebrating the campaign and symbolizing the Lyric’s future.

Eventually, Cosby raised more than $8 million via 89 donors — individuals, corporations and foundations — that contributed $10,000 or more. After historic tax credits were secured, the Lyric’s restoration fund reached $11.5 million. “The Lyric is a unique and beloved cause,” Cosby says. “I don’t know in my heart if (the donors) did it because they were such arts patrons — maybe they were — but I think they realized we needed a downtown for this area to thrive. … Places like the Lyric have absolute power and a sense of place. This is what separates Birmingham from a suburban strip mall.”

Executive director Beene — who’s been known to wax poetic about the Lyric, comparing it to a vintage instrument — also regards the theater’s revival as a no-nonsense economic development project. “We can’t afford to have a museum,” Beene says. “That’s not what we can do. From the start, I’ve said that we have to have an operating business for this to work.”

If his hopes for the Lyric are realized, the 750-seat theater will bring more people downtown, spurring growth and renewal that spreads for several blocks, transforming the area into a vibrant entertainment district. At the same time, Beene envisions the Lyric as a potent booster for civic pride.

“This is a place for all of our community to use, to share and to appreciate — not just as the past of Birmingham, but as the future of Birmingham,” he says. “We think that’s very important. … This gives people something to be proud of, something that’s unique, something to come home to. I want people to grow up at the Lyric. I want parents to bring their kids. I want youngsters to come there and see things. I want boyfriends to bring their girlfriends, and girlfriends to bring their boyfriends, and propose to them and get married on the stage. I want people to be swallowed up by the Lyric and enjoy it.”

That theme — the idea of “making modern memories” at the Lyric — comes up in conversation with all four of these key players, as Beene, Evans, Cosby and Brock continue their quest to make the theater shine again. Others who’ve become invested in the Lyric’s rebirth — board members, donors, volunteers, staffers and more — are likely to feel the same.

The restored Lyric Theatre opened to the public with three variety shows featuring local performers on Jan. 14-16, 2016. The task is far from finished. Beene, for example, can tick off a wish list for the Lyric that includes a green room, rehearsal spaces, expanded dressing rooms and a replica of the original box office. The adjoining office building? It hasn’t been touched yet.

Birmingham Landmarks also owns a building next-door to the Lyric that formerly housed the Majestic Theatre, a vaudeville competitor during the early 1900s. Two floors are empty, Beene says; the ground floor is home to Superior Furniture.

“We’ve got lots of dreams, but they’ll have to wait,” says Evans, the board chairman. “We need to get all the kinks worked out at the Lyric.” Ask Evans to retrace his steps back to 1993 and take a big-picture view, summing up how the Lyric was saved, and he responds without hesitation. The most important thing, he says, was taking an initial leap of faith. “The catalyst was when we decided to do it,” Evans says. “We didn’t know how to do it, and there was a lot of bumping into walls. But we made the decision to do it.”

Beene offers another perspective. “With heart,” he says. “That’s the short answer. If you put all the pieces together, it was timing, hometown people and others with a vision to know what the Lyric could be.”

The Birmingham Rewound website shows an ad for “Johnny Be Good” with Alan Freed and Chuck Berry showing at the Lyric in March 1960. That’s the last one I could find.

http://www.birminghamrewound.com/features/1960-03.htm

I missed that one, but I did go to the Lyric a few times as a kid. Saw “Earth Versus the Flying Saucers,” “The Werewolf,” “The Land Unknown,” and a few others in that cultural niche. I think the last one I saw there was a spin-off clone of “Jason and the Argonauts,” with a bunch of Italian body-builders but without the Ray Harryhausen animation, probably in 1959.

The Strand closed in late 1962. Rewound shows an article on the closing in December and an ad for “Tower of London” in November. I remember seeing that one, Vincent Price as Richard III in the last show at the Strand. I probably didn’t appreciate the full significance of it all at the time.

http://www.birminghamrewound.com/features/1962-12.htm

I was in Bham from summer 1954 to fall 1963, from age 9 to 18. The Strand was named the Newmar when I arrived and changed back to the Strand later. I don’t remember the Galax, the Royal, or the original Newmar/Capitol/Alcazar at all.

Birmingham Wiki page about the Lyric with photos.

http://www.bhamwiki.com/w/Lyric_Theatre

Covered in a BBC News article titled “Birmingham, Albama: A City Using Theatres to Reinvent Itself.”

Anyone know of the status of the projection equipment at the Lyric? Installed? Gone?

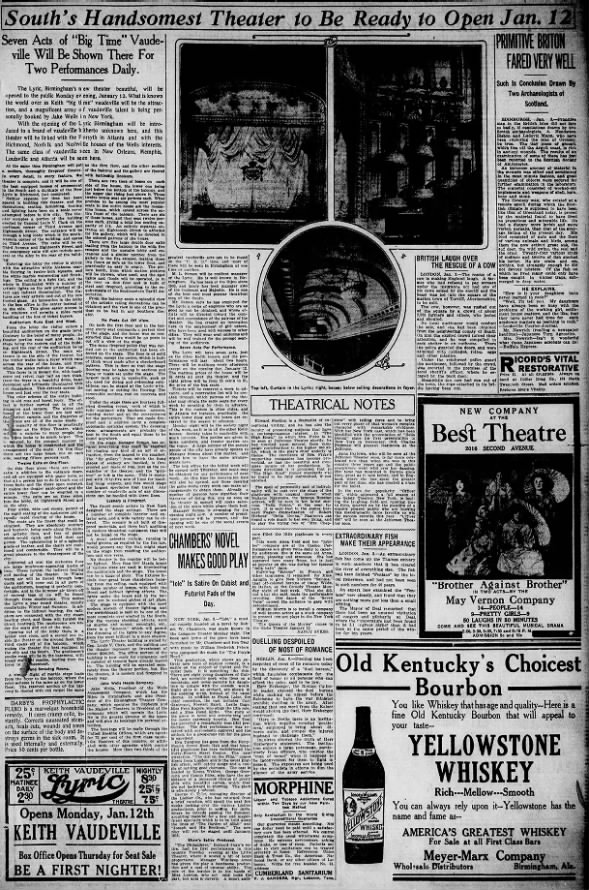

Grand opening ad and articles: Lyric theatre opening 04 Jan 1914, Sun The Birmingham News (Birmingham, Alabama) Newspapers.com

Lyric theatre opening 04 Jan 1914, Sun The Birmingham News (Birmingham, Alabama) Newspapers.com